DO WE LEARN FROM FAILURES?

Why do equipment failures keep happening?

You would have thought that the occurrence of failures in pressure equipment, lifting equipment and the like would have been just about eliminated by now. Companies have management procedures, feedback reports, safety procedures all bound up into all-encompassing Quality Systems covering just about everything. If you look at websites from the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and US Chemical Safety and Investigations Board (CSB) however you will see that serious failures are not uncommon. All industries try their hardest to put a brave face on things, but failures continue to happen.

Where is all the evidence that we learn from history?

Engineering failures seem to suffer from the same thorny problem as all historical events involving human experience; we don’t seem particularly good at learning well from them. In the world of industrial plant, meaningful failure statistics are hard to come by. Perhaps because of the wide variety of ‘failures’ that can happen it is just about impossible to find any evidence to suggest that failures are reducing. You may feel they are, and plant owners would like us to believe they are, but you will find actual objective evidence in short supply. So, what is the reason we don’t learn much from failures?

Why we don’t learn very well from others’ mistakes

This could be due, in part, to the way in which they are related to us. We learn about them through companies’ press releases and at presentations at Institution meetings and user-groups. In such forums, presentations made by the failed plant’s owners (the people who know the best what really happened) are carefully tailored to suggest that it probably wasn’t anyone’s fault, certainly not theirs.

Even if they have to tentatively admit it might have been their fault, they would like to think they were the unfortunate victim of circumstance. They are unlike to tell the gathered masses anything that shows them in a bad light. They are more likely to tell you about how it could have been a lot worse but wasn’t, so ‘didn’t they do well?’. Failure investigation reports, seminars and user group presentations are therefore rather like any kind of written history in the world, always kind to the people who wrote them.

What if someone else writes about a failure that has happened? Reports on failures written by uninformed third parties are subject to different, but equally effective barriers to not expressing the truth in the most comprehensive way possible. Newspaper and journal reports are written by people who have at best peripheral knowledge of any failure, because they weren’t there.

More formal reports by regulatory authorities get much nearer the technical truth but still, they weren’t there, and have to rely on the testimony of others, tempered by their own observations. Some, such as those from the CSB are excellent but they can’t cover all industries and work on limited resources. Also, those developing countries that have the most failures tend not to have such a well-organised system for reporting and analysing therm.

Legal cases are interesting. Read the conclusion of any legal case relating to an industrial failure and what you see is unlikely to relate the objective, ultimate, absolute technical truth. Whilst it is a brave attempt to conclude the truth, it’s more like a consistent version of one possible truth, not a description of the only one there is.

These are reasons why we perhaps don’t learn from failures as well as we would like to.

The best ‘truth’ about failures comes from big datasets

Some failure investigations get nearer the absolute truth than all the others. They are the ones that are collected and collated over time, and from big datasets from which feedback is reliably available. Examples of these are aircraft failures, motor vehicle accidents and the demise of people themselves. The lowest common denominator of the last two is insurance.

Vehicle and life insurance companies have a vested interest in when vehicles breakdown or are involved in accidents, and the same with people, so they end up with pretty much 100% accurate statistical datasets. It’s slightly different with aircraft, but with much the same results, which is why aircraft are incredibly mechanically reliable.

There’s a lot of failure information on pressure plant and lifting equipment around, but it’s not a fraction of one percent of what constitutes a statistically significant dataset. There’s no worldwide co-ordination of the dataset anyway; it’s completely fragmented over all the different plant owners and without a driving force (such as insurance risk) to draw it all together. All you see is good-looking fragments presented at Institution meetings and user-groups, and we have already seen how they work.

Can learning be improved?

The technical reasons behind failures are well known and documented. The other contributors; human factors are more elusive to pin down but again, are well known about. Put these optimistically-looking situations together however and the result is that we still don’t learn.

This leads to the conclusion that there must be some natural laws of organisations around that stops them learning from their own mistakes. If there wasn’t they would have sorted it out by now. It’s clear that having a big dataset helps, but for the businesses that don’t have that (most of them) then the learning ability of an organisation as an entity seems random, at best. They can learn for a short while it seems but seem doomed to soon reinvent the problems they had previously solved.

One way that does seem to work is subjecting the organisation to regulations. These can be Health and Safety Regulations or broader technical ones driven by engineering standards and codes. The fact that organisations are legally obliged to comply with regulations imposes the learning on them, making it work.

We are happy to say that there does seem to be evidence of this. The alternative, improvements due to self-regulation of industries is much talked about but, again, it is difficult to find any evidence that it actually works. It is difficult for any organisation to prove that whatever they did categorically caused a failure not to occur. It’s a bit like trying to prove a negative.

So how can the learning capability of organisations be improved? That’s way too big a question for us here at Matthews Integrity Hub: HEAD OFFICE. We are simple engineer-types. One way maybe would be to identify why your organisation doesn’t learn from failures and try doing the opposite. Alternatively check out these two links, compare the two, decide which one you believe, and base your actions on that,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organizational_learning

- www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/january-2005/how-do-we-learn-from-history

The good news

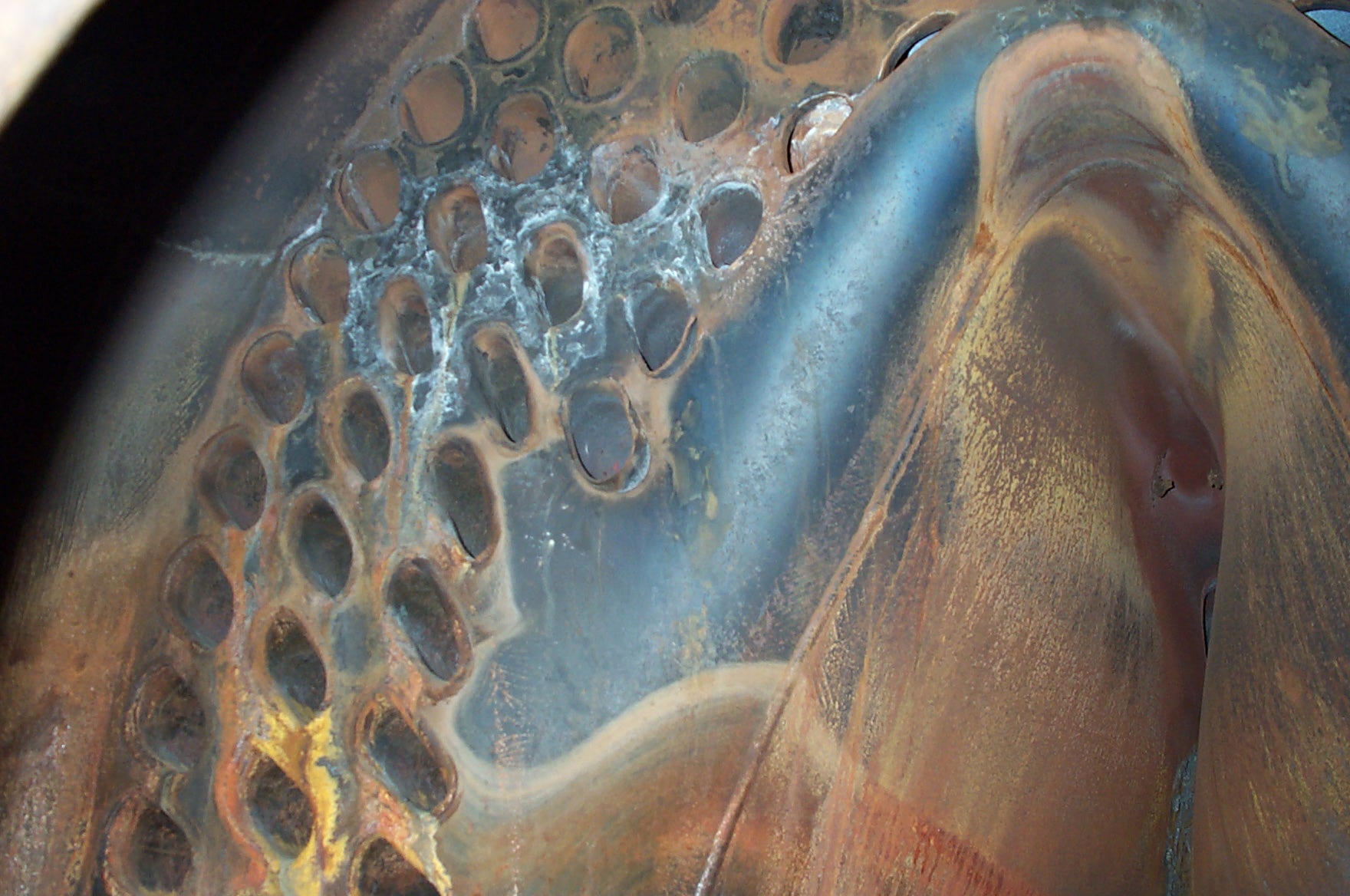

You’ve already heard the good news, twice. The reasons that engineering things fail about are well known about. In the pressure equipment world, corrosion, (particularly under insulation) fatigue, creep, SCC and erosion account for perhaps 80% of them. Low quality untested materials, repairs and out-of-code modifications probably cause about half the remaining 20% with the final 10% being related to operating error.

Improving things

The best place to start if you want to avoid future failures is simply to start off with the mindset that failures are avoidable and equipment is not likely to come up with new ways to fail that you have never heard of. They have all been seen before. Once you know what causes failures then you have moved a little way towards preventing them happening. You’ve got to be careful not to get ahead of yourself however; as we have said, accidents and failures happen for the same reasons again and again. Why not read our linked article; The cause of all accidents

You’ve also got to be careful not to get too convinced by the conclusions of fitness-for-purpose (FFP) studies carried out on severely corroded or damaged plant. Have a look at our linked article: FFP studies; the risks for some gentle warnings about these.

Matthews Integrity Hub: HEAD OFFICE is OPEN EVERY DAY….0730 – 2200 Monday – Sunday…That’s correct, all week, every week, including holidays

If we happen to miss your call, leave a message and we will call you back just as soon as we pick it up. Sorry, there’s no automated messages, call queueing, voice recognition tools or canned music. Try it and see.

If we happen to miss your call, leave a message and we will call you back just as soon as we pick it up. Sorry, there’s no automated messages, call queueing, voice recognition tools or canned music. Try it and see.

CONTACT US

Tel: 07746 771592 help@matthewsintegrity.co.uk